Chapter 3 in Dillenburger, K., O'Reilly, M.F., & Keenan, M. (Eds.) (1997). Advances in Behaviour Analysis. Dublin: University College Dublin Press, 236 pp. (ISBN 1-900621-08-8)

'W'-ing:

Teaching exercises for radical behaviourists

Mickey Keenan

Abstract

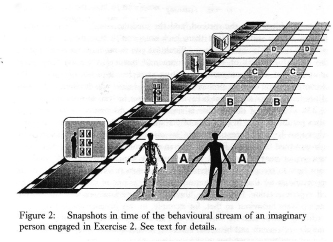

The widespread misrepresentation of radical behaviourism may be a reflection of the difficulties of teaching its views on private events. Consequently, this paper begins with a discussion of the behavioural stream and it contains exercises in self-observation that are intended to be used in classroom situations. Students who are actively encouraged to participate in self-observation under the guidance of a behavioural perspective may be more discerning of the seriousness of misrepresentation when it appears in their course of study.

Introduction

"Though vast in quantity, the great majority of behavioural findings tell us little of worth about ourselves. In a sense, having denied the importance of subjective data, their findings appear limited, alien, even 'soul-less'." (Spinelli, 1989, p. 175)

In recent years there have been attempts by members of the behavioural community to redress the type of serious misrepresentation quoted above (Catania, 1991; Lee, 1989; Lonigan, 1990; Morris, 1985, 1990; Wyatt, 1990). The primary objective of this paper is to contribute to the general debate about what should be done by offering suggestions for teaching exercises that address specific features of the philosophy of radical behaviourism.

The rationale for these exercises hinges on some of the problems incurred in the dissemination of conclusions reached by fellow scientists. Skinner (1989) touched on this issue when he said that "... everything scientists now do must at least once have been contingency shaped in someone, but most of the time scientists begin by following rules. Science is a vast verbal environment or culture" (p. 44). In that same chapter he discussed the differential effects of contingency-shaped and rule-governed behaviour. The points he made are relevant here because they contain general guidelines that may help in the design of effective methods for teaching:

"Those who have been directly exposed to contingencies behave more subtly and effectively than those who have merely been told, taught, or advised to behave or who follow rules. There is a difference because rules never fully describe the contingencies they were designed to replace. There is also a difference in the states of the body felt."(Skinner, 1989, p. 44)

Radical behaviourists distinguish their discipline from methodological behaviourism in terms of how they view private events (Hayes & Brownstein, 1987; Moore, 1980, 1981; Schneider & Morris, 1987; Skinner, 1953, 1974). This being the case it would seem reasonable to suppose that the behavioural community should produce teaching exercises concerned with the study of private events that take into account the observations outlined by Skinner. If teachers were provided with, for example, precise instructions for producing the type of differential behavioural effects described above, then the ways in which radical behaviourists resolve some of the difficult issues that arise in the study of private events would be open to inspection by students. Students who are exposed to well structured exercises along these lines may be then less likely to view radical behaviourists as 'contingency accountants' who are insensitive to the richness of human experience.

A second related objective of the exercises contained here is to stimulate others to contribute to the development of a wide range of teaching gambits for teachers of radical behaviourism. The development of such material would ensure that our teaching of scientific verbal behaviour is brought under strong discriminative control. Before describing the exercises, the next section of the paper contains a general overview of some of the issues that they were designed to address.

Teaching exercises for radical behaviourists

Mickey Keenan

Abstract

The widespread misrepresentation of radical behaviourism may be a reflection of the difficulties of teaching its views on private events. Consequently, this paper begins with a discussion of the behavioural stream and it contains exercises in self-observation that are intended to be used in classroom situations. Students who are actively encouraged to participate in self-observation under the guidance of a behavioural perspective may be more discerning of the seriousness of misrepresentation when it appears in their course of study.

Introduction

"Though vast in quantity, the great majority of behavioural findings tell us little of worth about ourselves. In a sense, having denied the importance of subjective data, their findings appear limited, alien, even 'soul-less'." (Spinelli, 1989, p. 175)

In recent years there have been attempts by members of the behavioural community to redress the type of serious misrepresentation quoted above (Catania, 1991; Lee, 1989; Lonigan, 1990; Morris, 1985, 1990; Wyatt, 1990). The primary objective of this paper is to contribute to the general debate about what should be done by offering suggestions for teaching exercises that address specific features of the philosophy of radical behaviourism.

The rationale for these exercises hinges on some of the problems incurred in the dissemination of conclusions reached by fellow scientists. Skinner (1989) touched on this issue when he said that "... everything scientists now do must at least once have been contingency shaped in someone, but most of the time scientists begin by following rules. Science is a vast verbal environment or culture" (p. 44). In that same chapter he discussed the differential effects of contingency-shaped and rule-governed behaviour. The points he made are relevant here because they contain general guidelines that may help in the design of effective methods for teaching:

"Those who have been directly exposed to contingencies behave more subtly and effectively than those who have merely been told, taught, or advised to behave or who follow rules. There is a difference because rules never fully describe the contingencies they were designed to replace. There is also a difference in the states of the body felt."(Skinner, 1989, p. 44)

Radical behaviourists distinguish their discipline from methodological behaviourism in terms of how they view private events (Hayes & Brownstein, 1987; Moore, 1980, 1981; Schneider & Morris, 1987; Skinner, 1953, 1974). This being the case it would seem reasonable to suppose that the behavioural community should produce teaching exercises concerned with the study of private events that take into account the observations outlined by Skinner. If teachers were provided with, for example, precise instructions for producing the type of differential behavioural effects described above, then the ways in which radical behaviourists resolve some of the difficult issues that arise in the study of private events would be open to inspection by students. Students who are exposed to well structured exercises along these lines may be then less likely to view radical behaviourists as 'contingency accountants' who are insensitive to the richness of human experience.

A second related objective of the exercises contained here is to stimulate others to contribute to the development of a wide range of teaching gambits for teachers of radical behaviourism. The development of such material would ensure that our teaching of scientific verbal behaviour is brought under strong discriminative control. Before describing the exercises, the next section of the paper contains a general overview of some of the issues that they were designed to address.

| w-ing.pdf | |

| File Size: | 1073 kb |

| File Type: | |